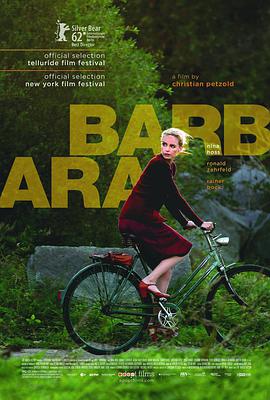

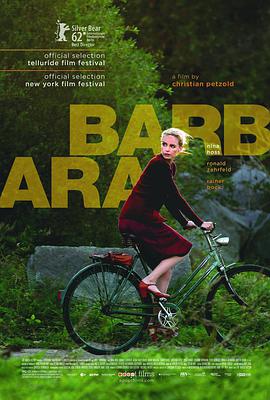

芭芭拉7.5

演员:Rainer Bock / Claudia Geisler / 霍斯 / 尼娜 / 策尔费尔德 / 罗纳尔德 / Christina Hecke

年份:2012-02-11

地区:内详

演员:Rainer Bock / Claudia Geisler / 霍斯 / 尼娜 / 策尔费尔德 / 罗纳尔德 / Christina Hecke

年份:2012-02-11

地区:内详

女医生Babara(尼娜·霍斯 Nina Hoss 饰)因为企图从民主德国逃到联邦德国未遂,而被从柏林调遣到一所乡村医院工作,一开始她根本不和周围的人来往,直到医生Andre(隆纳德·泽荷菲德 Ron